|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the more important geological areas on California's vast Mojave Desert can be explored near the southern end of Death Valley National Park in the Alexander Hills, roughly 20 miles southeast of Shoshone. Here Precambrian rocks have yielded incontrovertible evidence of early cellular life that constructed a shell, mineralized skeletal elements secreted by animate soft-bodied eukaryotic organisms over three-quarters of a billion years ago in a shallow marine environment then situated near the equator. Even though the extraordinary specimens are obviously minute, microscopic, recovered by invertebrate paleontologists from chert layers in a thick accumulation of dolomites, magnesium carbonate, their significance is regionally inestimable: some of the oldest examples of increasingly complex life on the Mojave Desert. In addition to fossil cells admittedly inaccessible to many amateur paleontology enthusiasts--isolating the miraculously preserved specimens requires special technical laboratory expertise in the practiced use of several potent acids, combined with access to mechanized equipment capable of slicing extremely hard samples of quartz chert into thin sections amenable for examination under a microscope--the Alexander Hills also offers visitors a different fossil type that is easily observed in the primordial Precambrian rock exposures: the fascinating stromatolites, distinctively laminated calcium carbonate structures created by photosynthesizing cyanobacterial blue-green algae approximately 1.2 billion years ago. These are quite probably the oldest fossil remains recognized from the meteorologically tortured Mojave Desert district--surprisingly well preserved specimens that occur in a readily accessible limestone reef. Of course, productive Precambrian paleontology is not the only adventure attraction available in the Alexander Hills. The district also offers many mineralogical delights: among them, high grade talc specimens from numerous workings left behind at the currently idle Western Talc Mine, one of the more prolific producer of talc in San Bernardino County, California, and certainly one of the most significant mining districts in all the Mojave Desert. But that's not all. There's more. Only a few miles from the Alexander Hills is fabulous Sperry Wash, where gem-quality agate and excellently preserved petrified wood can be observed. Although the well-known wood deposit has been heavily visited since its discovery in the late 1950s, exceptional material can still be discovered there. Also, along the route to the Alexander

Hills, you will have an opportunity to observe along both sides

of the road the drab brown sediments and occasional ledges of

whitish volcanic tuffs that accumulated in ancient Lake Tecopa.

The Tecopa rocks have been dated through geological determinations

at two hundred thousand to three million years old, or upper

Pliocene to midd1e Pleistocene on the geologic time scale. Roughly

225 feet of mudstones, conglomerates, volcanic ash, and shoreline

tufas were deposited in Lake Tecopa, only one of many large bodies

of fresh water that came into existence during interglacial periods

of the Pleistocene Epoch. In addition to documenting radiometrically dated volcanic tuff beds, earth scientists have also recovered a significant vertebrate and invertebrate fossil fauna from the ancient Lake Tecopa Basin. The late Pliocene-Pleistocene animals include mammoths, a mastodon, large and small horses, a llama, camels, a large antelope, abundant microtine rodents (the voles, lemmings, and muskrats), and a flamingo. Also identified have been ostracods (a diminutive bivalved crustacean), gastropods, 42 species of diatoms (microscopic photosynthesizing single celled algae), and chara (a green algae), all of which confirm a lacustrine environment. Amateur collectors beware, though. Under current regulations, it is illegal to collect any vertebrate fossil without a special use permit, a document issued solely to individuals with a minimum B.S. degree from an accredited university (or museum representatives with appropriate credentials) who seek to undertake formal scientific research projects that can be fully verified as authentic by the petitioned authorities. Qualified folks wishing to apply for such a permit must contact the State Director of the Bureau of Land Management in Sacramento, California. An excellent reference to consult concerning the geology of the Tecopa area is United States Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Map I-728 by John W. Hillhouse, Late Tertiary and Quaternary Geology of the Tecopa Basin, Southeastern California. The Alexander Hills geologic district hosts a world renouned geologic sequence of mostly conformable Late Precambrian through Early Cambrian strata--that is to say, geologists have identified up to 14,800 feet of very well exposed sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous material approximately 1.3 billion to 520 million years old, in which relatively few recognizable breaks in geologic time interrupt the exceedingly ancient geochronogogical stratigraphic succession. Rock formations present in the Alexander Hills include some of the most iconic geologic units in all the US southwest. Oldest is the Precambrian/Mezoproterozoic Crystal Spring Formation some 1.3 to 1.08 billion years old (side bar: Precambrian supercontinent Rodinia began to assemble 1.26 billion to 900 million years ago). Although many geologists assign the upper member of the Crystal Spring Formation to a distinct, separate geologic rock unit called the Horse Thief Spring Formation (approximately760 to 802 million year old), an excellent technical paper issued in 2019 convincingly demonstrated that the Horse Thief Spring interval is older than 1.08 billion years old, and so by inference it must surely remain a continuation of the Crystal Spring Formation. Not only that, but the author of a 2015 Ph.D. dissertation on Precambrian units in the Death Valley region could not corroborate the findings of the person who had erected the new Horse Thief Spring Formation in the first place, only a year earlier in 2014. The 2015 researcher found no detrital zircon grains from the Horse Thief Spring Formation that matched the geologic age of those that the year 2014 person had apparently recovered to help prove his case; that 2014 rsearcher had supposedly foumd zirons dated at 780 million years, which would support a great disconformity in the Crystal Spring Formation. Yet, after examining 540 zircon grains from five different geologic sections (zircons amenable to age-dating are mighty difficult to locate and isolate, in the first place), the 2015 investigator determined that all his zircons from the Horse Thief Spring samples were over one billion years old, thus falsifying the 2014 person's claim of a younger age. Funny thing is, though: That 2015 individual continued to accept the Horse Thief Spring Formation as valid throughout his dissertation. Next up is the overlying Beck Spring Dolomite, around 787 to 732 million years old. The dominantly magnesium carbonate sequence contains stromatolites and numerous kinds of eukaryotic cells, including vase-shaped microfossils produced by a testate shell-secreting amoeba; a chert layer near the base of the Beck Spring Dolomite yielded one of the oldest shells in the fossil record, a skeletal element from one of those testate amoeba dated at roughly 780 million years old--called scientifically, Cycliocyrillium. For geochronological perspective, the oldest known evidence of a shell-bearing organism comes from the 809 million year old Fifteenmile Group in Yukon, Canada. Note of course that there is a significant unconformity between deposition of the Crystal Spring Formation and the Beck Spring Dolomite. And something else was happening at about this time. From 750 to 633 million years ago, the Precambrian supercontinent Rodinia broke apart, when several great interlocked landmasses that would later form North America, South America, Antarctica, Australia, Siberia, China, and India began to drift away. Lying directly above the Beck Spring Dolomite is the Kingston Peak Formation--roughly 732 to 700 million years old. Originally deposited in marine waters near the equator, it's a regionally remarkable rock unit that bears at least three distinct horizons comprised of diamictites and tills, distinctively diagnostic accumulations that indicate deposition by glacial activity--direct evidence of a so-called Snowball Earth, when ice sheets extended all the way to low tropical latitudes. The Kingston Peak also yields stromatolites and microscopic eukaryotic cells, some of which have been identified as testate amoebae of vase-shaped morphological configuration. Stratigraphically speaking, the Crystal Spring Formation, Beck Spring Dolomite and Kingston Peak Formation are conveniently lumped together in the widespread Pahrump Group. Directly above the Pahrump sedimentary assemblage is the Noonday Dolomite (about 680 to 630 million years old--famously yields quite sizable stromatolitc structures); note once again that there is an unconformity between the Kingston Peak Formation and the Noonday Dolomite, afterwhich deposition of the overlying Johnnie Formation (630 to 580 million years old) coincides with the assembly of another Precambrian supercontinent called Pannotia 633 to 573 million years ago; Pannotia was rather short-lived geologically speaking, though, as it began to break up approximately 560 million years ago. The youngest Alexander Hills stratigraphic units are the Stirling Quartzite, some 580 to 544 million years old, which bears an important Ediacaran age fauna within its youngest phases of deposition, and the late Neoproterozoic to lower Cambrian Wood Canyon Formation, 544 to 520 million years old; a Neoproterozoic horizon in the lower Wood Canyon strata also yields Ediacaran fossils, while early Cambrian sections produce the first trilobite remains in the local stratigraphic section. Although the early Cambrian strata that outcrop here are admittedly not as fossiliferous as those of correlative stratigraphic age at classic Waucoba Spring, Inyo County, California (as of 1994, assimilated into Death Valley National Park, so that unauthorized fossil collecting there is now strictly verboten), the Alexander Hills reference section still provides exceptional opportunies for geologists, geophysists, stratigraphers, and invertebrate paleontologists to study the important Precambrian-Cambrian transition boundary. Of the several geologic rock units exposed in the Alexander Hills, only the Wood Canyon Formation contains remains of animals with hard parts recognizable with the unaided eye, principally trilobite fragments, occasional archaeocyathids (extinct calcareous sponge), and poorly preserved but paleontologically invaluable disarticulated echinodern plates, specimens that could very well be the oldest echinoderm evidence yet identified. Ichnofossils identified from the Alexander Hills paleontological district include excellently preserved tracks and trails of annelids and arthropods (some of which probably represent trilobitic activity on the ancient sea floor over a half billion years ago). Not far from the primary locality in the Alexander Hills, you will observe excellent outcrops of the Neoproterozoic Beck Spring Dolomite, a massively bedded magnesium carbonate that accumulated in an intertidal region of a vast, shallow sea some 787 to 732 million years ago. From a casual distance the Beck Spring hillside perhaps appears to project just another monotonous rock deposit in the middle of the desert; but within those drab gray to bluish dolomites occur some of the oldest known eucaryotic cells in the southwestern US--in other words, cells with a well organized encapsulated nucleus, a feature which distinguishes them from primitive prokaryotic bacteria and the archaea. Animals, plants, fungi, algae, and protists, for example, all possess eukaryotic cells. The Beck Spring fossil cells were discovered under the microscope in thin sections of chert interbedded in the dominantly dolomitic section; they are of course not the oldest eukaryotes ever discovered. Such unambiguous eukaryotic cells go back about 1.8 billion years in the geologic record (controversial evidence of their presence begins at about 2.1 million years), but when first reported in a scientific paper in 1969 they were considered for a short spell at least to represent the oldest eukaryotes ever found. In North America, earliest eukaryotic existence occurs in the roughly 1.4 billion year old Mesoproterozoic Greyson Formation of northern Montana and southern British Columbia, Canada. The Beck Spring fossil association is dominated by filamentous cyanophycean algae (the blue-green algae), with at least five genera that resemble modern chlorophytes (green algae) and chrysophtes (golden-brown algae). Their presence here constitutes a truly miraculous preservational occurrence, since soft-bodied organisms have been identified from but a minimal number of localities around the globe; ergo, the discovery of such fragile microscopic cells roughly three-quarter of a billion years old certainly rates as a phenomenal event. The Beck Spring Dolomite also figures prominently in a most intriguing idea, indeed. Namely, that land life already existed on Earth over a billion years ago. Not too long ago, geotechnical explorations in the Death Valley National Park region produced tantalizing evidence to help support the hypothesis that abundant photosynthetic microbial communities had already colonized terrestrial habitats some 1.2 to 750 million years ago. Too, supplemental geochemical and paleontological documentation from different terrestrial deposits approximately 2.2 billion years old (not present in the Death Valley area) suggests that land-living photosynthesizing organisms could have contributed substantially to the great oxygenation event that began approximately 2.3 billion years ago. Of course, just to provide that proverbial "truth in advertising" qualifier, while many investigators with reluctant resignation now appreciate that significant microbial terrestrial life existed in the Neoproterozoic, not a few earth scientists continue to express a natural skeptical dubiety, unwilling to agree that land-life older than around 600 million years is incontrovertible fact. But, that dramatically distant terrestrial microbial existence is difficult to disprove with definitive convincingness, because leading proponent Paul Knauth, geochemist-geologist with Arizona State University, not only believes he has the significant carbon isotope signatures from such primordial Precambrian deposits to help support the idea, but also loads of fossil, microscopic photosynthetic organisms secured from thin-sectioned rocks of proved karstic, terrestrial origin, roughly 1.2 billion to 750 million years ancient, including important collections from the world-famous 750 million-year old Beck Spring Dolomite (Death Valley National Park region), a magnesium carbonate accumultion that of course overlies the cyanobacterial stromatolitic developments present in calcium carbonate exposures of the 1.2 billion year-old Crystal Spring Formation. But that's not the conclusion of the story. Not at all. Not only does Paul Knauth adduce abundant evidence to support pre-600 million-year old microbial land colonization, he also firmly advocates the potentially provocative postulation that animal life on Earth originated not in the sea, but within terrestrial environs; subjectively compelling evidence supports the existence of land-living multi-cellular animals devouring peacefully co-existing 750 million year-old photosynthetic microbial communities, just minding their own business, pumping important quantities of oxygen into Earth's ancient atmosphere. After stopping for a look-see at the Neoproterozoic Beck Spring Dolomite in the Alexander Hills, continue onward toward the main fossil site, which in addition to stromatolite beds in the Mesoproterozoic Crystal Spring Formation also contains deposits of high grade commercial talc exposed by the Western Talc mining operations. The Precambrian fossil material occurs in that impressive reef-like ridge/peak before you, a prominent paleontological protuberance some 5,000 feet long that preserves locally comman stromatolites through some 300 feet of pure calcium carbonate, limestone, in the 1.2 billion year old Crystal Spring Formation. Just up ahead from where you will park is a huge "hole in the ground" adjacent to an intrusive diabase sill dated at 1.08 billion years old, dramatic evidence of extensive open pit mining operations that obviously removed tons of talc over a period of numerous years. It is but one of many large-scale excavations found throughout the Alexander Hills, all part of the much famous Western Talc Mine, an aggregation of 11 separate claims that have operated off and on since the early 1900s. All the mines are silently idle at present, although most remain under patent subject to potentially productive redevelopment when commercial exploitation of mineral commodites becomes more reliably profitable. The earliest workings in the Alexander Hills were made in 1912 by the Independent Sewer Pipe Company, an outfit that went out of business in 1914. In the following eight years, several different companies tried their hand at the rich talc bodies, including successively: the Tropico Tile and Terra Cotta Company; the Pacific Talc and Terra Cotta Company; the Pacific Minerals and Chemical Company; and the Tropico Potteries Company. All of these ventures belonged to a single organization headed by one A, Lindsay, who also owned the active claims and directed the first major operation, originally known as the Acme or Lindsay mine. Lindsay's mining speculation failed in 1923, but a former business associate named Martin decided to lease the property and continue exploration. Martin organized the Master Minerals Corporation, which eventually became the Martin Minerals Company, and in 1923 the newly formed Western Talc and Magnesite Company struck glory-hole magnitude talc in the Snow Goose claims in a previously undeveloped portion of the deposit. By the mid 1920s talc production was well under way in the Alexander Hills. In 1928, Fred Savell, president of the Western Talc and Magnesite Company, bought out the Martin Minerals Cermpany and consolidated all the active claims of both businesses under one name--the Western TaIc Mine, which continued to produce talc through 1959; up to that time 310,000 tons had been taken from the Alexander Hills. An excellent reference work on the talc bodies of southeastern California, in general, is California Division of Mines and Geology Special Report number 95, 1968, by Lauren A. Wright, TaIc Deposits of the Southern Death Valley-Kingston Range Region, California. Professor Wright discusses all of the major talc mines in this part of the Mojave Desert, presenting the geology and history of exploration of each deposit in readily readable fashion. It is indeed a classic of mineralogical literature. The fossil-bearing exposures of the Crystal Spring Formation occur along the moderately steep slopes of the massive limestone "reef" immediately east of the open pit talc mines. Here can be found rather common and surprisingly well preserved stromatolites (considering the considerable geologic stress they've experienced since their burial 1.2 billion years old), distinctively laminated calcium carbonate structures formed through successive layering by photosynthetic cyanobacterial blue-green algae. And while they are certainly not the oldest stromatolites identified in the fossil record--a suggestive indication of stromatolitic presence approximately 3.5 billion years ago does indeed exist in western Australia--the Alexander Hills examples nevertheless promote sober contemplation and inspirational awe--direct evidence of life some 1.2 billion years old, more than a full quarter the age of the Earth itself (which formed 4.5 billion years ago), microscopic life that first helped oxygenate our atmosphere, providing the crucial elemental gas that allowed us to exist. Today, similar kinds of stromatolites grow in Sharks Bay off the coast of Australia, where low tides expose distinctive dome-like bodies whose internal structure is identical to the fossil varieties. The stomatolites in the Crystal Spring Formation do not represent the actual mineralized remnants of the once living gelatinous cyanobacteria, but rather they resulted from sediment trapped by the algae approximately 1.2 billion years ago. As each fragile layer of algae regularly disappeared beneath a veneer of calcareous sediment, a new algal surface would eventually develop atop the older one just buried, until successive concentrlc laminations developed over perhaps hundreds of years; in modern stomatolite growth cycles, when covered by sediment, the cyanobacteria instinctively migrate to the surface to find sunlight and continue their photosynthetic ways. After the Crystal Spring sediments became lithified during the course of geologic time, the unusual layering created by successive cyanobacterial colonies became preserved in the rocks. Today, roughly one billion two-hundred-million years later, stromatolies preserved in the Precambrian Crystal Spring Formation probably remain quite similar to what they would have looked like in actual life all those eons ago. Important side bar: Biologically speaking, stromatolites do not develop from algal activity. They are not algae, though colloquial convention perpetuates the technically incorrect use of the word "algae" to describe them; still and all, calling them algae is certainly not a taxonomical "criminal offense." It's just what most folks most often call them. And so it's all good. The fossil stromatolites are not hard to spot at this Alexander Hills reef locality. They appear as circular to oval concentrically laminated structures a few inches to a foot in diameter. Erosion has frequently exposed them in bold, eye-catching relief against the pale gray limestones, and numerous chunks of quality cyanobacteria-bearing materal lie scattered about, fractured off the bedrock. When found in situ, a few of the stromatolitic algae heads reveal an elliptical profile, a feature which suggests that they grew in ocean waters strongly influenced by currents. Most of the stromatolite species, though, indicate a rather placid shallow intertidal or subtidal paleoenvironment. Two prevalent stromatolite varieties in the Crystal Spring Formation have been identified by paleontologists as Baicalia and Conophyton, genera previously identified in Precambrian rocks 1.35 billion to 900 million years old in other parts of the world. In a historical perspective, establishing a precise geologic age for the Alexander Hills stromatolites has certainly presented a serious challenge. First off, it is happily well and good that over the years every Crystal Spring investigator could at least agree, could so stipulate as it were, that the cyanobacterial developments occur within a sedimentary section cut by an intrusive diabase sill of igneous origin. But that general consensus inevitably led to an obvious question: Just how old is that diabase sill? For decades, disagreements abounded, until sophisticated radiometric methodology finally established a definitive geologic age of 1.08 billion yeas for the diabase sill; that meant of course that the Crystal Spring Formation stromatolies must be older than 1.08 billion years, since the cyanobacterial creations were obviously already in place when the diabase sill intruded the sedimentary section within which they occur. Then too, because basement crystalline rocks that underlie the Crystal Spring Formation in the southern Death Valley area can be correlated with similar regional lithologies that yield radiometric dates of 1.7 to 1.4 billion years, the ultimate upshot is that after additionally factoring in the relative stratigraphic position of the stromatolites within the Crystal Spring Formation, well above the basement complex, most earth scientists now agree that the geologic age of the Crystal Spring Formation stromatolites is 1.2 billion years old. One of the influential Alexander Hills stromatolite investigators was David G. Howell, formerly of the University of California at Santa Barbara. Howell took a series of thin sections of stromatolites from the Crystal Spring Formation and produced amazing three dimensional reconstructions of what the original cyanobacterial homes must have looked like. In 1971, he reported his findings in the important paper, A Stromatolite from the Proterozoic Pahrump Group, Eastern California, Journal of Paleontology, volume 45, number one, pages 48 to 51. Another excellent reference paper concerning stromatolites is Columnar Stromatolites and Late Precambrian Stratigraphy by M.E. Raaben, American Journal of science, volume 267, January 1969. For several years, Raaben was associated with the Geological Institute, Academy of Sciences in Moscow. His report details a wide assortment of stromatolites present in Precambrian rocks in the defunct Soviet Union, specimens Raaben had hoped would help establish a systematized intercontinental stratigraphic model to correlate stromatolite-bearing strata around the world. One of the better technical reports available regarding stromatolites in the Crystal Spring Formation is Stratigraphy and Depositional Environment of the Crystal Spring Formation, southern Death valley Region, California by Michael T. Roberts, an article contained in California Division of Mines and Geology special Report 106, 1976, Geologic Features, Death Valley, California. An accurate detailed geologic map of the area is Map Sheet number 77, Geology of the Alexander Hills Area, Inyo and San Bernardino Counties, California, by Lauren A. Wright, found in the California Division of Mines and Geology Bulletin 170, Geology of Death Valley, California. After examining one billion two hundred million year old stromatolites, it's time for a trip to nearby Sperry Wash, one of the most famous petrified palm wood localities on the Mojave Desert. It's a region that also yields many well preserved tracks of extinct camels and horses, plus the relatively rare (in the geologic record) remains of silicified grasses. Along the way, you will pass large-scale mining operations that produce obvious concentrations of commercial grade talc, and it is indeed tempting to wander off the main route to explore the impressiuve abandoned pits left behind when the mining \venture fell flat. But heed the No Trespassing signs where applicable. Much of this area remains under claim, sitting idle, anticipating further exploitation of mineral commodities. By general agreement among gem seekers, Sperry Wash is a fascinating area to explore. The wash slices through sandstones, mudstones, and conglomerates of the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation, dated at 10.3 to 8.4 million years old. Petrified palm and dicotlyedon wood (birch and poplar have been identified), grasses replaced by silicon dioxide (assigned to Tomlinsonia stichkaniam, whose closest modern analogs belong to the bahiagrasses, genus Paspalum, which utilize the C4 carbon fixation photosynthetic process--only three percent of modern terrestrial plants use the C4 pathway), horse and camel tracks (from an extinct species called Lamaichnum macropodum--at last check, the excellent museum in Shoshone has on display several tracks from China Ranch camels and horses), and attractive agates occur within silicified fine-grained sediments that happily preserve in fine detail the majority of Miocene permineralized plants present here. According to Mary Frances Strong in the November 1975 issue of Desert Magazine (long out of business--July 1985 was their last month of publication), Aileen Mckinney discovered the Sperry Wash wood bonanza in 1956; Strong wrote the first article to describe the site for the January 1958 edition of Gems and Minerals Magazine, a publication that went belly-up not a few years ago. Since that time Sperry Wash has taken on an almost mythical reputation among rockhounds; many collectors rate the variety of petrified palm wood found at other localities on a standard set by the high quality they've encountered in Sperry Wash. Other folks are content to wax nostalgic for the wonderful wood formerly collected there. While it's true that the once unbelievable quantity of wood and gem-grade agate is a matter of fond recollection in the minds of many who were there in the "early days," rest assured that excellent material remains to be discovered. It just takes a little longer to find the better quality petrified wood now that the years of frequent visitation have caught up with Sperry Wash. Traditionally speaking, the Alexander Hills are most comfortably visited in early to mid spring and mid to late fall; sometimes early winter can be fun, too, although sudden ferocious winds with concomitant plunging wind chill factors often ruin an otherwise perfect outing, especially if you are "braving the elements" in a tent or simply sleeping outdoors under the stars. One of my favorite trips, though, actually came in the midst of winter, when I spent a full week camped at the base of the Precambrian stromatolite-bearing reef. I was all alone with the desert--not one other individual appeared along the Western Talc Road during that memorable seven day period. I spent most of my time hiking about, exploring the great limestone reef and the numerous talc mines that penetrate the Alexander Hills. Once, I recall, I finally managed to climb to the very top of that massive mound of ancient algae, and I sat there with chunks of weather-sculpted stromatolitic rock all around me. From this position, I vividly remember watching a lone bird soar on a thermal far above me as a warm rush of wind whipped eroded limestone grains against the stromatolite exposure. I wondered if a similar breeze had brushed the waters of a shallow sea over a billion years ago where I now rested, nudging gentle waves over gelatinous algal bodies anchored in the deep distance of vanished time when our sun shone some eight percent dimmer than at present, thinking too that if those humble microscopic life forms had not pumped out oxygen with unceasing cyanobacterial photosynthetic productivity, silently venting through the eons an elemental waste gas initially inimical to the cellular metabolism of Earth's early emergent complex animacules--until, finally, persistent natural adaptation fatally allowed more advanced organisms to utilize oxygen, to multiply and abound and ultimately conquer--stromatolites might have remained the dominate form of life on Earth. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A view southward to the stromatolite-bearing reef in the Precambrian Crystal Spring Formation (1.2 billion years old)--the isolated peak at upper center--Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. Whitish area at base is waste rock left behind by operations at the Western Talc Mine. Green lettering BSD designates an excellent outcrop of the 787 to 732 million year old Beck Spring Dolomite, which yields some of the oldest eukaryotic cells in the western US. Right--A closer look at the Precambrian stromatolite-bearing locality in the Alexander Hills; whitish waste debris from the Western Talc Mine seen at base of the peak. Viewing perspective is southward. Photographs originally taken with a Minolta 35mm camera. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Seekers of paleontological adventure explore stromatolite-bearing exposures of the 1.2 billion year old Precambrian Crystal Spring Formation. Image at left taken a short distance from the Alexander Hills in Inyo County, California. Picture at right snapped in the Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. Photographs originally taken with a Minolta 35mm camera. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A desert adventurer examines a huge pit created when the Western Talc Company removed enormous quantities of high grade talc from the Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. Right--Paleontologically motivated folks rest atop a lower Cambrian section of the Precambrian-Lower Cambrian Wood Canyon Formation (here, around 520 million years old) at a locality near the Alexander Hills. The Wood Canyon strata here yield plentiful annelid and arthropod trails and tracks (ichnofossils), in addition to coquinas comprised almost entirely of disarticulated plates from an early echinoderm--perhaps the oldest evidence of echinoderms in the fossil reocord. Trilobites and archaeocyathids (extinct calareous sponge) have also been reported from the lower Cambrian facies of the Wood Canyon Formation. Photographs originally taken with a Minolta 35mm camera. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--An investigator of the Precambrian holds stromatolites from the 1.2 billion year old Crystal Spring Formation. Stromatolite-bearing reef in the Alexander Hills in background. Photograph courtesy Michael Wing. Right--A view northeast across the slopes of the stromatolite-yielding reef in the Precambrian Crystal Spring Formation, Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. Photograph courtesy Ben Waggoner. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Field examples of the 787 to 732 million year old Neoproterozoic Beck Spring Dolomite that outcrop several miles from the Alexander Hills. The Beck Spring Dolomite yields some of the oldest skeletonized eukaryotic cells yet discovered in the US west. Image at right shows strontium-enriched giant ooids, characteristic of a specific horizon in the Beck Spring Dolomite. Ooids usually develop from concentric carbonate accretion around a minute sand fragment (or, a shell in modern oceans) in warm, shallow, extremely agitated marine intertidal environments. Photographs courtesy Robert Clyde Mahon. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Exposures of the roughly three million to 200,000 year old Tecopa Lake Beds along the route to the Alexander Hills. The late Pliocene-Pleistocene sediments yield a rich assortmant of fossil remains, including mammoths, a mastodon, large and small horses, a llama, camels, a large antelope, abundant microtine rodents (the voles, lemmings, and muskrats), and a flamingo. Also identified have been ostracods (a tiny bivalved crustacean), gastropods, 42 species of diatoms--microscopic photosynthesizing single celled algae--and chara (a green algae), all of which confirm a lacustrine environment. Google Earth Street Car perspectives that I edited and processed through photoshop. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Views from Sperry Wash, not far from the Alexander Hills, where the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation, dated at 10.3 to 8.4 million years old, yields petrified woods (including palm and dicotyledons), grasses replaced by silicon dioxide (assigned to the species Tomlinsonia stichkania), and horse and camel tracks (from an extinct species called Lamaichnum macropodum--at last check, the excellent museum in Shoshone has on display several tracks from China Ranch camels and horses). Photo at left courtesy an individual who goes by the cybername PSHiker. Image at right courtesy a person who goes by the cyberhandle Octopup. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--The green arrows point to the tops of domed stromatolites, created by photosynthesizing cyanobacterial activity, in the 1.2 billion year old Mesoproterozoic Crystal Spring Formation, Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Domed stromatolites from the Mesoproterozoic Crystal Spring Formation, Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. The stromatolites were created by photosynthesizing cyanobacteria some 1.2 billion years ago. Photograph at left courtesy Michael Wing; image at right courtesy Jonathon Marcot. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Stromatolites from the Mesoproterozoic Crystal Spring Formation, 1.2 billion years old. Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. Photographs courtesy hawkwind3141 (left) and Ben Waggoner (right). |

|

|

|

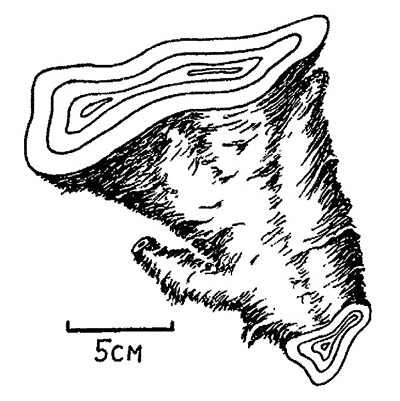

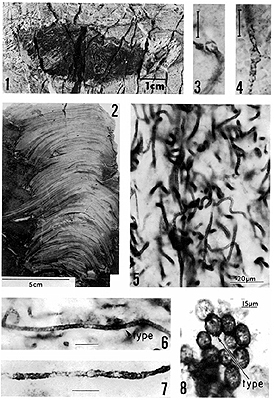

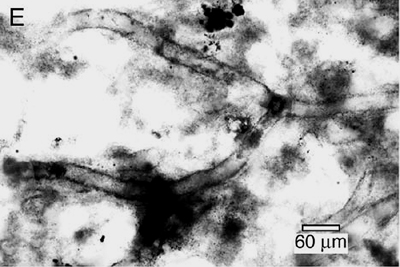

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A three dimensional reconstruction of a stromatolite from the Mesoproterozoic Crystal Spring Formation of 1.2 billion years ago. 5cm scale bar represents slightly less than two inches. Photograph courtesy David G. Howell. Right--Eukaryotic microfossils photographed in thin sections of cherts from the 787 to 732 million year old Neoproterozoic Beck Spring Dolomite. The Beck Spring eukaryote fauna is dominated by filamentous cyanophycean algae (the blue-green algae), with at least five genera that resemble modern chlorophytes (green algae) and chrysophtes (golden-brown algae). Photograph courtesy Gerald R. Licari, formerly a professor of geology at East Los Angeles College, California. Legend for the image at right. For measurements in microns (signified by the symbol µm), one micron equals one twenty-five thousandth of an inch. One centimeter equals about 0.4 inch:  |

|

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Eukaryotic microfossils photographed in thin sections of cherts from the 787 to 732 million year old Neoproterozoic Beck Spring Dolomite. The Beck Spring eukaryote fauna is dominated by filamentous cyanophycean algae (the blue-green algae), with at least five genera that resemble modern chlorophytes (green algae) and chrysophtes (golden-brown algae). Photograph courtesy Gerald R. Licari, formerly a professor of geology at East Los Angeles College, California. Legend for the image at left. For measurements in microns (signified by the symbol µm), one micron equals one twenty-five thousandth of an inch:  Legend for the image at right. For measurements in microns (signified by the symbol µm), one micron equals one twenty-five thousandth of an inch:  |

|

|

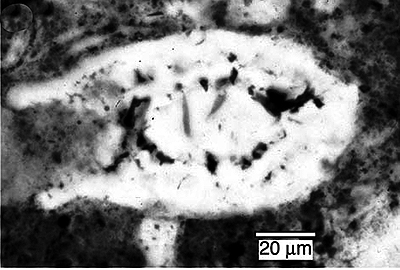

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Microfossils from the Neoproterozoic Beck Spring Dolomite (about 740 million years old). Secured from a locality several miles from the Alexander Hills, California. Both are mere microns in actual length, as viewed under a microscope; one micron equals one twenty-five thousandth of an inch. They're skeletal elements (shells) of eukaryotic protistans, possibly allied with arcellinid testate amoebae. Photographs courtesy Leigh Anne Riedman, Susannah M. Porter, and Andrew D. Czaja. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Microfossil from the Neoproterozoic Beck Spring Dolomite (about 780 million years old). Note that the scale bar is in microns; one micron--designated by the symbol µm-- equals one twenty-five thousandth of an inch. It's the minute shell of a testate amoeba eukaryotic cell called scientifically Cycliocyrillium. Photograph courtesy an anonymous individual. Right--Microfossil from the Neoproterozoic Kingson Peak Formation, around 732 million years old. Secured from a locality several miles from the Alexander Hills. It's the shell of a testate amoeba eukaryotic cell called scientically, Melanocyrillium. Photograph courtesy Frank A. Corsetti, Stanley M. Awramik, and David Pierce. |

|

|

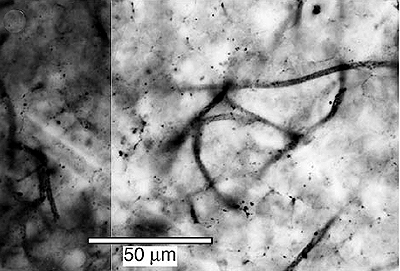

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Microfossils from the Neoproterozoic Kingston Peak Formation (about 730 million years old), deposited during Snowball Earth when our planet experienced profound glaciation all the way to equatorial sectors. Secured from a locality several miles east of the Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. Note that the scale bar is in microns; one micron--designated by the symbol µm-- equals one twenty-five thousandth of an inch. Left--Filamentous microfossils, probably cyanobacteria. Right--A large branching filament assigned to the genus Paeoleosiphonella, a probable autotrophic eukaryote. Photographs courtesy Frank A. Corsetti, Stanley M. Awramik, and David Pierce. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Annelid trails (ichnofossils) from the lower Cambrian section of the late Precambrian-lower Cambrian Wood Canyon Formation, from a locality in Inyo County, California, not far from the Alexander Hills. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--An Olenellus sp. trilobite cephalon from the lower Cambrian section of the late Precambrian-lower Cambrian Wood Canyon Formation, Death Valley National Park, Inyo County, California. Photograph by Martin Miller, University of Oregon, courtesy of the Earth Science World Image Bank. Right--A coquina composed of disarticulated echinoderm plates (grayish structures in reddish matrix) from the lower Cambrian section of the late Precambrian-lower Cambrian Wood Canyon Formation. From locality in Inyo County, California, not far from the Alexander Hills. These could well represent the oldest evidence of echinoderms in the fossil record. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Ediacaran fossils from the late Proterozoic lower member of the Wood Canyon Formation, roughly 544 million years old--three million years prior to the beginning the Cambrian Period (and the Paleozoic Era) 541 million years ago. Specimens at left called scientifically Cloudina (they also resemble the Ediacaran genus Conotubus from the late Neoproterozoic Deep Spring Formation, western Nevada). At right is Swartpuntia germsi. Collected by paleontologists James W. Hagadorn and Ben Waggoner from exposures near Johnnie in neighboring Nye County, Nevada. Photographs courtesy James W. Hagadorn and Ben Waggoner. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A mammoth lower jaw and tooth, from the late Pliocene to Pleistocene Tecopa Lake Beds, Inyo County, California. Called scientifically, genus Mammuthus sp. Photograph taken in 2002 at the museum in Shoshone, California, where the specimens were on display. Right--Partially articulated camel bones in a plaster jacket, collected by technicians from the late Pliocene to Pleistocene Tecopa Lake Beds, Inyo County, California. Called scientifically, Capricamelus gettyi. Photograph courtesy a specific technical document. |

|

|

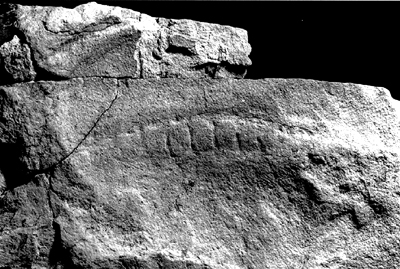

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Vertebrate fossils from the late Pliocene to Pleistocene Tecopa Lake Beds, Inyo County, California, on display at the museum in Shoshone, California. Labeled specimens include lower jaw, tusks and a thoracic vertebra from a mammoth (Mammuthus sp.), plus a mastodon scapula; the remains are Pleistocene in geologic age, roughly 600,000 years old. Right--Horse and camel tracks from the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation, dated at 10.3 to 8.4 million years old. The camel is called scientifically, Lamaichnum macropodum. In addition to mammal tracks (ichnofossils), the China Ranch Formation also yields petrified palm and dicotlyedon wood (birch and poplar have been identified) and silicified grasses (replaced by silicon dioxide) assigned to the species Tomlinsonia stichkania. Images courtesy Vanessa Hamrick, who captured them at the museum in Shoshone, California, in 2023. |

|

|

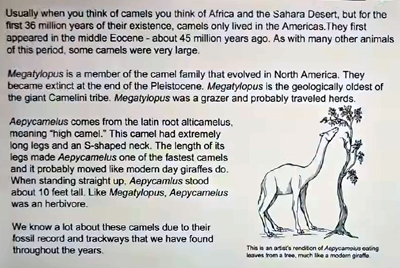

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--A cast of a fossil Mastodon tooth originally collected from the Pliocene-Pleistocene Tecopa Lake Beds, roughly 600,000 years old, along side a minature replica of a mastodon skeleton. Right--A diorama about camel species that left behind fossil tracks in the middle Miocene China Ranch Formation. In addition to mammal tracks (ichnofossils), the China Ranch Formation also yields petrified palm and dicotlyedon wood (birch and poplar have been identified) and silicified grasses (replaced by silicon dioxide) assigned to the species Tomlinsonia stichkania. Images courtesy Wonderhussy Adventures, from a video shot at the museum in Shoshone, California, in 2023. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Camel and horse tracks from the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation, dated at 10.3 to 8.4 million years old. Called scientifically, Lamaichnum macropodum. In addition to mammal tracks (ichnofossils), the China Ranch Formation also yields petrified palm and dicotlyedon wood (birch and poplar have been identified) and silicified grasses (replaced by silicon dioxide) assigned to the species Tomlinsonia stichkania. Photograph taken in 2002 at the museum in Shoshone, California, where the specimens were on display. Right--A compressed petrified palm stump from the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation, dated at 10.3 to 8.4 million years old. From Sperry Wash, San Bernardino County, California. Photograph courtesy Douglas Moore. |

|

|

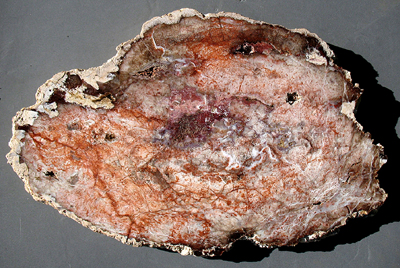

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--petrified wood from the late Miocene China Lake Formation, Sperry Wash, San Bernardino County, California. Specimen is at left is from a dicotlyedon; paleobotanical remain at right is silcified palm. Both photographs courtesy Douglas Moore. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Petrified palm wood from the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation, dated at 10.3 to 8.4 million years old. Collected from Sperry Wash, San Bernardino County, California. Photographs courtesy Douglas Moore. |

a.jpg) |

|

|

Click on the images for larger pictures. Left--Petrified palm wood from the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation, dated at 10.3 to 8.4 million years old. Collected from Sperry Wash, San Bernardino County, California. Photograph by a person who goes by the cybername of Alan. Right--A sampler of goodies from the Alexander Hills district. Top row: All from the late Miocene China Ranch Formation (10.3 to 8.4 million years old) of Sperry Wash, San Bernardino County, California. Far left is an agatized limb cast. Remaining specimens are agates. Middle row--three talc specimens from the vicinity of the Western Talc Mine, Alexander Hills, San Bernardino County, California. Bottom row--silicified palm fiber from the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation (10.3 to 8.4 million years old) of Sperry Wash, San Bernardino County, California. |

|

|

| Click on the images for larger pictures. Left and right--Permineralized, silicified, grasses from the late middle Miocene China Ranch Formation, dated at 10.3 to 8.4 million years old. Collected from Sperry Wash, San Bernardino County, California. Called scientifically, Tomlinsonia stichkania Left--Transverse section of a culm (the stem) with surrounding leaf sheaths. Right--Transverse section containing several grass plant specimens. Photographs courtesy William D. Tidwell and E. M. V. Nambudiri. |

|

The Acoustic Guitar Solitaire Of Inyo: A Cyber-CD: I play 30 covers of some of my favorite songs on an acoustic 6-string guitar; it's all free music. Beyond The Timberline--A Cyber-CD: I play 32 selections comprised of covers and original tunes on acoustic 6 and 12-string guitars; it's all free music. The Distant Path--A Cyber-CD: I play 32 acoustic guitar covers and original compositions; it's all free music. Inyo And Folks--A Musical History--A Quintuple Cyber-CD: My parents and I play 203 selections; it's all free music. Acoustic Stratigraphy--A Cyber-CD: I play 34 covers of some of my favorite songs on 6 and 12-string guitars; it's all free music. Back To Badwater--A Cyber-CD: I play 32 covers and original compositions on 6 and 12-string guitars; it's all free music. All Inyo All The Time: All six of my cyber-cds in one place (includes a quintuple cyber-cd box set); links to all of my solo acoustic guitar playing, in addition to selections my parents and I recorded during the Golden Age of our spontaneous, impromptu recording sessions. Includes an option to stream all 364 selectons; thirteen hours, seventeen minues and forty seconds of music (it's all free music). It's A Happening Thing--Music From The Year 1967: All songs that charted US Billboard Hot 100 (#1 to #100) and Bubbling Under (records that charted in positions #101 to #135) in 1967. Fossils In Death Valley National Park: A site dedicated to the paleontology, geology, and natural wonders of Death Valley National Park; lots of on-site photographs of scenic localities within the park; images of fossils specimens; links to many virtual field trips of fossil-bearing interest. Fossil Insects And Vertebrates On The Mojave Desert, California: Journey to two world-famous fossil sites in the middle Miocene Barstow Formation: one locality yields upwards of 50 species of fully three-dimensional, silicified freshwater insects, arachnids, and crustaceans that can be dissolved free and intact from calcareous concretions; a second Barstow Formation district provides vertebrate paleontologists with one of the greatest concentrations of Miocene mammal fossils yet recovered from North America--it's the type locality for the Bartovian State of the Miocene Epoch, 15.9 to 12.5 million years ago, with which all geologically time-equivalent rocks in North American are compared. A Visit To Fossil Valley, Great Basin Desert, Nevada: Take a virtual field trip to a Nevada locality that yields the most complete, diverse, fossil assemblage of terrestrial Miocene plants and animals known from North America--and perhaps the world, as well. Yields insects, leaves, seeds, conifer needles and twigs, flowering structures, pollens, petrified wood, diatoms, algal bodies, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, bird feathers, fish, gastropods, pelecypods (bivalves), and ostracods. Fossils At Red Rock Canyon State Park, California: Visit wildly colorful Red Rock Canyon State Park on California's northern Mojave Desert, approximately 130 miles north of Los Angeles--scene of innumerable Hollywood film productions and commercials over the years--where the Middle to Late Miocene (13 to 7 million years old) Dove Spring Formation, along with a classic deposit of petrified woods, yields one of the great terrestrial, land-deposited Miocene vertebrate fossil faunas in all the western United States. Cambrian And Ordovician Fossils At Extinction Canyon, Nevada: Visit a site in Nevada's Great Basin Desert that yields locally common whole and mostly complete early Cambrian trilobites, in addition to other extinct organisms such as graptolites (early hemichordate), salterella (small conical critter placed in the phylum Agmata), Lidaconus (diminutive tusk-shaped shell of unestablished zoological affinity), Girvanella (photosynthesizing cyanobacterial algae), and Caryocaris (a bivalved crustacean). Late Pennsylvanian Fossils In Kansas: Travel to the midwestern plains to discover the classic late Pennsylvanian fossil wealth of Kansas--abundant, supremely well-preserved associations of such invertebrate animals as brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, echinoderms, fusulinids, mollusks (gastropods, pelecypods, cephalopods, scaphopods), and sponges; one of the great places on the planet to find fossils some 307 to 299 million years old. Fossil Plants Of The Ione Basin, California: Head to Amador County in the western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada to explore the fossil leaf-bearing Middle Eocene Ione Formation of the Ione Basin. This is a completely undescribed fossil flora from a geologically fascinating district that produces not only paleobotanically invaluable suites of fossil leaves, but also world-renowned commercial deposits of silica sand, high-grade kaolinite clay and the extraordinarily rare Montan Wax-rich lignites (a type of low grade coal). Ice Age Fossils At Santa Barbara, California--Journey to the famed So Cal coastal community of Santa Barbara (about a 100 miles north of Los Angeles) to explore one of the best marine Pleistocene invertebrate fossil-bearing areas on the west coast of the United States; that's where the middle Pleistocene Santa Barbara Formation yields nearly 400 species of pelecypod bivalve mollusks, gastropods, chitons, scaphopods, pteropods, brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, ostracods (minute bivalve crustaceans), worm tubes, and foraminifers. Trilobites In The Marble Mountains, Mojave Desert, California: Take a trip to the place that first inspired my life-long fascination and interest in fossils--the classic trilobite quarry in the Lower Cambrian Latham Shale, in the Marble Mountains of California's Mojave Desert. It's a special place, now included in the rather recently established Trilobite Wilderness, where some 21 species of ancient plants and animals have been found--including trilobites, an echinoderm, a coelenterate, mollusks, blue-green algae and brachiopods. Fossil Plants In The Neighborhood Of Reno, Nevada: Visit two famous fossil plant localities in the Great Basin Desert near Reno, Nevada--a place to find leaves, seeds, needles, foilage, and cones in the middle Miocene Pyramid and Chloropagus Formations, 15.6 and 14.8 to 13.3 million years old, respectively. Dinosaur-Age Fossil Leaves At Del Puerto Creek, California: Journey to the western edge of California's Great Central Valley to explore a classic fossil leaf locality in an upper Cretaceous section of the upper Cretaceous to Paleocene Moreno Formation; the plants you find there lived during the day of the dinosaur. Early Cambrian Fossils Of Westgard Pass, California: Visit the Westgard Pass area, a world-renowned geologic wonderland several miles east of Big Pine, California, in the neighboring White-Inyo Mountains, to examine one of the best places in the world to find archaeocyathids--an enigmatic invertebrate animal that went extinct some 510 million years ago, never surviving past the early Cambrian; also present there in rocks over a half billion years old are locally common trilobites, plus annelid and arthropod trails, and early echinoderms. Plant Fossils At The La Porte Hydraulic Gold Mine, California: Journey to a long-abandoned hydraulic gold mine in the neighborhood of La Porte, northern Sierra Nevada, California, to explore the upper Eocene La Porte Tuff, which yields some 43 species of Cenozoic plants, mainly a bounty of beautifully preserved leaves 34.2 million years old. A Visit To Ammonite Canyon, Nevada: Explore one of the best-exposed, most complete fossiliferous marine late Triassic through early Jurassic geologic sections in the world--a place where the important end-time Triassic mass extinction has been preserved in the paleontological record. Lots of key species of ammonites, brachiopods, corals, gastropods and pelecypods. Fossil Plants At The Chalk Bluff Hydraulic Gold Mine, California: Take a field trip to the Chalk Bluff hydraulic gold mine, western foothills of California's Sierra Nevada, for leaves, seeds, flowering structures, and petrified wood from some 70 species of middle Eocene plants. Fossils In Millard County, Utah: Take virtual field trips to two world-famous fossil localities in Millard County, Utah--Wheeler Amphitheater in the trilobite-bearing middle Cambrian Wheeler Shale; and Fossil Mountain in the brachiopod-ostracod-gastropod-echinoderm-trilobite rich lower Ordovician Pogonip Group. Fossil Plants, Insects And Frogs In The Vicinity Of Virginia City, Nevada: Journey to a western Nevada badlands district near Virginia City and the Comstock Lode to discover a bonanza of paleontology in the late middle Miocene Coal Valley Formation. Paleozoic Era Fossils At Mazourka Canyon, Inyo County, California: Visit a productive Paleozoic Era fossil-bearing area near Independence, California--along the east side of California's Owens Valley, with the great Sierra Nevada as a dramatic backdrop--a paleontologically fascinating place that yields a great assortment of invertebrate animals. Late Triassic Ichthyosaur And Invertebrate Fossils In Nevada: Journey to two classic, world-famous fossil localities in the Upper Triassic Luning Formation of Nevada--Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park and Coral Reef Canyon. At Berlin-Ichthyosaur, observe in-situ the remains of several gigantic ichthyosaur skeletons preserved in a fossil quarry; then head out into the hills, outside the state park, to find plentiful pelecypods, gastropods, brachiopods and ammonoids. At Coral Reef Canyon, find an amazing abundance of corals, sponges, brachiopods, echinoids (sea urchins), pelecypods, gastropods, belemnites and ammonoids. Fossils From The Kettleman Hills, California: Visit one of California's premiere Pliocene-age (approximately 4.5 to 2.0 million years old) fossil localities--the Kettleman Hills, which lie along the western edge of California's Great Central Valley northwest of Bakersfield. This is where innumerable sand dollars, pectens, oysters, gastropods, "bulbous fish growths" and pelecypods occur in the Etchegoin, San Joaquin and Tulare Formations. Field Trip To The Kettleman Hills Fossil District, California: Take a virtual field trip to a classic site on the western side of California's Great Central Valley, roughly 80 miles northwest of Bakersfield, where several Pliocene-age (roughly 4.5 to 2 million years old) geologic rock formations yield a wealth of diverse, abundant fossil material--sand dollars, scallop shells, oysters, gastropods and "bulbous fish growths" (fossil bony tumors--found nowhere else, save the Kettleman Hills), among many other paleontological remains. A Visit To The Sharktooth Hill Bone Bed, Southern California: Travel to the dusty hills near Bakersfield, California, along the eastern side of the Great Central Valley in the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada, to explore the world-famous Sharktooth Hill Bone Bed, a Middle Miocene marine deposit some 16 to 15 million years old that yields over a hundred species of sharks, rays, bony fishes, and sea mammals from a geologic rock formation called the Round Mountain Silt Member of the Temblor Formation; this is the most prolific marine, vertebrate fossil-bearing Middle Miocene deposit in the world. High Sierra Nevada Fossil Plants, Alpine County, California: Visit a remote fossil leaf and petrified wood locality in the Sierra Nevada, at an altitude over 8,600 feet, slightly above the local timberline, to find 7 million year-old specimens of cypress, Douglas-fir, White fir, evergreen live oak, and giant sequoia, among others. In Search Of Fossils In The Tin Mountain Limestone, California: Journey to the Death Valley area of Inyo County, California, to explore the highly fossiliferous Lower Mississippian Tin Mountain Limestone; visit three localities that provide easy access to a roughly 358 million year-old calcium carbate accumulation that contains well preserved corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, and ostracods--among other major groups of invertebrate animals. Middle Triassic Ammonoids From Nevada: Travel to a world-famous fossil locality in the Great Basin Desert of Nevada, a specific place that yields some 41 species of ammonoids, in addition to five species of pelecypods and four varieties of belemnites from the Middle Triassic Prida Formation, which is roughly 235 million years old; many paleontologists consider this specific site the single best Middle Triassic, late Anisian Stage ammonoid locality in the world. All told, the Prida Formation yields 68 species of ammonoids spanning the entire Middle Triassic age, or roughly 241 to 227 million years ago. Late Miocene Fossil Leaves At Verdi, Washoe County, Nevada: Explore a fascinating fossil leaf locality not far from Reno, Nevada; find 18 species of plants that prove that 5.8 million years ago this part of the western Great Basin Desert would have resembled, floristically, California's lush green Gold Country, from Placerville south to Jackson. Fossils Along The Loneliest Road In America: Investigate the extraordinary fossil wealth along some 230 miles of The Loneliest Road In America--US Highway 50 from the vicinity of Eureka, Nevada, to Delta in Millard County, Utah. Includes on-site images and photographs of representative fossils (with detailed explanatory text captions) from every geologic rock deposit I have personally explored in the neighborhood of that stretch of Great Basin asphalt. The paleontologic material ranges in geologic age from the middle Eocene (about 48 million years ago) to middle Cambrian (approximately 505 million years old). Fossil Bones In The Coso Range, Inyo County, California: Visit the Coso Range Wilderness, west of Death Valley National Park at the southern end of California's Owens Valley, where vertebrate fossils some 4.8 to 3.0 million years old can be observed in the Pliocene-age Coso Formation: It's a paleontologically significant place that yields many species of mammals, including the remains of Equus simplicidens, the Hagerman Horse, named for its spectacular occurrences at Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Idaho; Equus simplicidens is considered the earliest known member of the genus Equus, which includes the modern horse and all other equids. Field Trip To A Vertebrate Fossil Locality In The Coso Range, California: Take a cyber-visit to the famous bone-bearing Pliocene Coso Formation, Coso Mountains, Inyo County, California; includes detailed text for the field trip, plus on-site images and photographs of vertebrate fossils. Fossil Plants At Aldrich Hill, Western Nevada: Take a field trip to western Nevada, in the vicinity of Yerington, to famous Aldrich Hill, where one can collect some 35 species of ancient plants--leaves, seeds and twigs--from the Middle Miocene Aldirch Station Formation, roughly 12 to 13 million years old. Find the leaves of evergreen live oak, willow, and Catalina Ironwood (which today is restricted in its natural habitat solely to the Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California), among others, plus the seeds of many kinds of conifers, including spruce; expect to find the twigs of Giant Sequoias, too. Fossils From Pleistocene Lake Manix, California: Explore the badlands of the Manix Lake Beds on California's Mojave Desert, an Upper Pleistocene deposit that produces abundant fossil remains from the silts and sands left behind by a great fresh water lake, roughly 350,000 to 19,000 years old--the Manix Beds yield many species of fresh water mollusks (gastropods and pelecypods), skeletal elements from fish (the Tui Mojave Chub and Three-Spine Stickleback), plus roughly 50 species of mammals and birds, many of which can also be found in the incredible, world-famous La Brea Tar Pits of Los Angeles. Field Trip To Pleistocene Lake Manix, California: Go on a virtual field trip to the classic, fossiliferous badlands carved in the Upper Pleistocene Manix Formation, Mojave Desert, California. It's a special place that yields beaucoup fossil remains, including fresh water mollusks, fish (the Mojave Tui Chub), birds and mammals. Trilobites In The Nopah Range, Inyo County, California: Travel to a locality well outside the boundaries of Death Valley National Park to collect trilobites in the Lower Cambrian Pyramid Shale Member of the Carrara Formation. Ammonoids At Union Wash, California: Explore ammonoid-rich Union Wash near Lone Pine, California, in the shadows of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States. Union Wash is a ne plus ultra place to find Early Triassic ammonoids in California. The extinct cephalopods occur in abundance in the Lower Triassic Union Wash Formation, with the dramatic back-drop of the glacier-gouged Sierra Nevada skyline in view to the immediate west. A Visit To The Fossil Beds At Union Wash, Inyo County California: A virtual field trip to the fabulous ammonoid accumulations in the Lower Triassic Union Wash Formation, Inyo County, California--situated in the shadows of Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States. Ordovician Fossils At The Great Beatty Mudmound, Nevada: Visit a classic 475-million-year-old fossil locality in the vicinity of Beatty, Nevada, only a few miles east of Death Valley National Park; here, the fossils occur in the Middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone at a prominent Mudmound/Biohern. Lots of fossils can be found there, including silicified brachiopods, trilobites, nautiloids, echinoderms, bryozoans, ostracodes and conodonts. Paleobotanical Field Trip To The Sailor Flat Hydraulic Gold Mine, California: Journey on a day of paleobotanical discovery with the FarWest Science Foundation to the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada--to famous Sailor Flat, an abandoned hydraulic gold mine of the mid to late 1800s, where members of the foundation collect fossil leaves from the "chocolate" shales of the Middle Eocene auriferous gravels; all significant specimens go to the archival paleobotanical collections at the University California Museum Of Paleontology in Berkeley. Early Cambrian Fossils In Western Nevada: Explore a 518-million-year-old fossil locality several miles north of Death Valley National Park, in Esmeralda County, Nevada, where the Lower Cambrian Harkless Formation yields the largest single assemblage of Early Cambrian trilobites yet described from a specific fossil locality in North America; the locality also yields archeocyathids (an extinct sponge), plus salterella (the "ice-cream cone fossil"--an extinct conical animal placed into its own unique phylum, called Agmata), brachiopods and invertebrate tracks and trails. Fossil Leaves And Seeds In West-Central Nevada: Take a field trip to the Middlegate Hills area in west-central Nevada. It's a place where the Middle Miocene Middlegate Formation provides paleobotany enthusiasts with some 64 species of fossil plant remains, including the leaves of evergreen live oak, tanbark oak, bigleaf maple, and paper birch--plus the twigs of giant sequoias and the winged seeds from a spruce. Ordovician Fossils In The Toquima Range, Nevada: Explore the Toquima Range in central Nevada--a locality that yields abundant graptolites in the Lower to Middle Ordovician Vinini Formation, plus a diverse fauna of brachiopods, sponges, bryozoans, echinoderms and ostracodes from the Middle Ordovician Antelope Valley Limestone. Fossil Plants In The Dead Camel Range, Nevada: Visit a remote site in the vicinity of Fallon, Nevada, where the Middle Miocene Desert Peak Formation provides paleobotany enthusiasts with 22 species of nicely preserved leaves from a variety of deciduous trees and evergreen live oaks, in addition to samaras (winged seeds), needles and twigs from several types of conifers. Early Triassic Ammonoid Fossils In Nevada: Visit the two remote localities in Nevada that yield abundant, well-preserved ammonoids in the Lower Triassic Thaynes Formation, some 240 million years old--one of the sites just happens to be the single finest Early Triassic ammonoid locality in North America. Fossil Plants At Buffalo Canyon, Nevada: Explore the wilds of west-central Nevada, a number of miles from Fallon, where the Middle Miocene Buffalo Canyon Formation yields to seekers of paleontology some 54 species of deciduous and coniferous varieties of 15-million-year-old leaves, seeds and twigs from such varieties as spruce, fir, pine, ash, maple, zelkova, willow and evergreen live oak High Inyo Mountains Fossils, California: Take a ride to the crest of the High Inyo Mountains to find abundant ammonoids and pelecypods--plus, some shark teeth and terrestrial plants in the Upper Mississippian Chainman Shale, roughly 325 million years old. Field Trip To The Copper Basin Fossil Flora, Nevada: Visit a remote region in Nevada, where the Late Eocene Dead Horse Tuff provides seekers of paleobotany with some 42 species of ancient plants, roughly 39 to 40 million years old, including the leaves of alder, tanbark oak, Oregon grape and sassafras. Fossil Plants And Insects At Bull Run, Nevada: Head into the deep backcountry of Nevada to collect fossils from the famous Late Eocene Chicken Creek Formation, which yields, in addition to abundant fossil fly larvae, a paleobotanically wonderful association of winged seeds and fascicles (bundles of needles) from many species of conifers, including fir, pine, spruce, larch, hemlock and cypress. The plants are some 37 million old and represent an essentially pure montane conifer forest, one of the very few such fossil occurrences in the Tertiary Period of the United States. A Visit To The Early Cambrian Waucoba Spring Geologic Section, California: Journey to the northwestern sector of Death Valley National Park to explore the classic, world-famous Waucoba Spring Early Cambrian geologic section, first described by the pioneering paleontologist C.D. Walcott in the late 1800s; surprisingly well preserved 540-510 million-year-old remains of trilobites, invertebrate tracks and trails, Girvanella algal oncolites and archeocyathids (an extinct variety of sponge) can be observed in situ. Petrified Wood From The Shinarump Conglomerate: An image of a chunk of petrified wood I collected from the Upper Triassic Shinarump Conglomerate, outside of Dinosaur National Monument, Colorado. Fossil Giant Sequoia Foliage From Nevada: Images of the youngest fossil foliage from a giant sequoia ever discovered in the geologic record--the specimen is Lower Pliocene in geologic age, around 5 million years old. Some Favorite Fossil Brachiopods Of Mine: Images of several fossil brachiopods I have collected over the years from Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic-age rocks. For information on what can and cannot be collected legally from America's Public Lands, take a look at Fossils On America's Public Lands and Collecting On Public Lands--brochures that the Bureau Of Land Management has allowed me to transcribe. In Search Of Vanished Ages--Field Trips To Fossil Localities In California, Nevada, And Utah--My fossils-related field trips in full print book form (pdf). 98,703 words (equivalent to a medium-size hard cover work of non-fiction); 250 printed pages (equivalent to about 380 pages in hard cover book form); 27 chapters; 30 individual field trips to places of paleontological interest; 60 photographs--representative on-site images and pictures of fossils from each locality visited. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 264-J: Fossils Birds From Manix Lake California, by Hildegarde Howard. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1928: Stratigraphy of the Lower And Middle(?) Triassic Union Wash Formation, East-Central California by Paul Stone, Calvin H. Stevens, and Michael J. Orchard. United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 483-F: An Unusual Lower Cambrian Trilobite Fauna From Nevada by Allison R. Palmer. United States Geological Survey Bulletin 1527: Age Of The Coso Formation, Inyo County, California by C. R. Bacon, D. M. Giovannetti, W. A. Duffield, W. A. Dalrymple and R. E. Drake. |